A Practical Guide to Navigating Your Quarter-Life Crisis

Written by Nick Noble

Edited by John Druga

February 17, 2021

There are thousands of articles out there about how 2020 has been an insane year. No doubt countless more will be written about 2021. Our society is changing rapidly. There are smart people talking about the collapse of western civilization, and equally good takes on how our collective coming-of age-growing pains are good for us. It’s hard to know who to trust and the changes have affected various groups in divergent ways. The global pandemic has disproportionately impacted poor and minority communities, while the protest movements aim for real long-term justice. The breakdown of American and global institutions is probably bad for everybody, but it brings hope that they can be rebuilt better. The privileged all over the world, and I count myself among them, have been forced to challenge themselves to understand the world in a new way.

Many of us are experiencing this societal coming of age with our own personal ones; be it entering high school, college, the workforce, or even retirement. Or maybe it is just coming to terms with being an adult. We are overlaying our own identity crises, or growing pains, on our cultures. In many cases, these personal transitions were catalyzed by the external events of 2020, and in others they were simply coincident.

As I write this, I’m going through my own version of it, a quarter-life crisis per see. I’m not sure whether this will be a good read for anyone, or just healthy catharsis for me. My situation is somewhat exaggerated by some very back-and-forth career moves, in-and-out relationships, and ever-changing cities. It also fits the model neatly because I happen to be 25 years old. However, many, if not most, of my close friends are grappling with the same questions. I want to take a deep dive into the phenomena everyone I know seems to be going through and determine if I can bring some clarity or practical thoughts to the situation, or maybe just start a dialogue about it with some of you.

To the extent that this is a critique of anything, it is a systemic one (Appendix A). All of my recent employers, or more notably leaders at those organizations, have been amazingly supportive as I’ve crossed this terrain. Moreover, my friends, family, and other close relationships have been my most important asset.

BREAKING DOWN THE “QUARTER LIFE CRISIS”

I think the term quarter-life crisis captures the nature of our experience quite well. You can find a dozen definitions on the internet. I like the one on Collins dictionary for its simplicity and generality. This is a phenomenon that hits everyone differently.

a crisis that may be experienced in one’s twenties, involving anxiety over the direction and quality of one’s life

I also appreciate Dr. Alex Fowke’s definition as well, in that it’s a bit more cutting. It is even hard to read if you’re in the middle of it yourself. It calls out how it can impact your thinking about every important area of your life, and I would not necessarily limit it to the list there.

a period of insecurity, doubt and disappointment surrounding your career, relationships and financial situation

Age is just a number in this case, and if you are closer to 40 than 25 it’s just called a midlife crisis. It’s something most people go through, typically multiple times, and seems to be a package deal with any tendency to overthink. The more ambitious, or maybe just the more thoughtful you are, the more likely you are to experience it and the harder it can hit you. The nature of these crises often involves tough questions about your career, your dating life, your social life, your values, and a million other things in difficult and intertwining ways. To make matters worse it can often be coincident with tough material conditions.

The earliest forms of this type of crisis happen in school, where we learn to fit in. These years involve hard questions. What AP classes should I take? Should I text this girl or boy? Is it OK to smoke pot? Will I make the baseball team? Does anyone like me? That’s just to name a few. Not long after that, the stakes are raised significantly and can start to involve six figure loans, real opportunity costs and lifetime commitments: Where should I go to college? What should I major in? Am I ready for a long-term relationship? Where should I work when I graduate?

These are wickedly hard choices that could by itself be the subject of a blog post, or a whole book. Many people experience the quarter-life crisis in college, and I have several very close friends who went through brutal soul searching during this period of their lives.

A lot of us though, myself included, went through some difficult transitions but were mostly able to punt on the really hard questions in college and high school. One characteristic that does differentiate those earlier transitions, especially for those of us that it was not super difficult for, from later identity crises is that the questions are often multiple choice. Whether it happens in high school or college or in retirement, as you grow older you start getting hit with more open ended, more fundamental questions:

- What am I good at? What could I be world-class at, if anything?

- How important is money, and how much do I need? How about fame? Legacy? Being interesting?

- How important are my hobbies? Would I give them up for a great career? A great relationship?

- Am I proud of what I do? Is what I am doing helping people? Does that matter to me?

- Do I love this person? Would I move for them? Would I make sacrifices in my career to be with them? Would they do the same for me and is that important?

Some of these new questions are not a one-time deal, but ongoing dilemmas that can only be tackled with daily practice and advanced planning. Some of them are very practical, others more ethereal, while the truly difficult ones are both. Everyone has a slightly different set of questions, so strategies can’t even be compared. The answers to these questions and the choices you make with those answers will not only have a huge material impact on you, and even on generations to come, but the answers will go on to shape your identity and self-image. The stakes are really high, and they feel even higher. More often than not any choice you make will involve difficult tradeoffs, and accepting that is a big part of the crisis.

BREATHE: IT IS OKAY

The most insidious element of the quarter-life crisis isn’t the self-doubt, momentary choice paralysis, or difficult tradeoffs. All of that is natural and you will overcome it. The most insidious element is that it can make you not love yourself through the process. It can put you on a deferred life plan and can get you saying and thinking things like “I’ll be happy when…I’m rich, appreciated, fulfilled…when I figure this out.”

If you are to read any sentence here, read the next one. Cut yourself a break, it’s OK. Being hard on yourself is of zero practical value and dealing with these questions and making hard choices is a symptom of the options you have, likely through years of hard work. Be proud of that. Furthermore, figuring these things out is not easy for anyone, and if it being difficult is a symptom of you being thoughtful, of you caring, of you wanting to do the right thing, then you should be proud of that too.

But it cuts even deeper. We are going through this during a civilizational coming of age, during a time in which we are seeing just how unjust our society can be and just how broken our institutions are. As every generation matures, it is charged with challenging the status quo and building a better world. In many instances, we become adults and discover options to do that are not available, or quite difficult to access. We find many small ways to help but also discover that in other important areas of our life there is not much that can be done, or when there is, we still must wait for a seat at the adult table. Again, to be bucking against this is a symptom of being thoughtful, that you care, and that you want to fight the good fight. Be proud of that and keep fighting. In a society that is sick, that is deeply unjust, to totally fit in is not a sign of health or success.

We need to reject the deferred life plan and learn to develop strategies to accept the uncertainty, and to thrive in it. We can and will navigate these waters and learn to make good choices, or perhaps make some bad ones and then course correct to better ones. We can do all this and build up unique skill sets and networks that will pay dividends long after this moment has passed. Perhaps most importantly, we need to figure out how to truly enjoy the process and take these years back from our worst thought patterns.

IMPERMANENCE AND FEAR SETTING

Everything you do at this moment feels like the most consequential thing in the world; just like making the baseball team, or asking that girl out, or choosing a major did. To be clear some choices are very materially consequential. In many cases choosing that major, or not choosing one, will have a huge impact on the rest of your career and your future income. There are also objectively bad choices. Drug addictions, needless high interest debt, and a few other bad moves can snowball terribly and in the worst cases can kill you.

If you have a specific goal in life, to be the best in a particular field, to get a particularly high level degree or a job at a specific company, you may need to follow a precise path. That comes with its own extreme difficulties but you’re likely not going through the kind of crises I’m talking about. In fact, there is a good chance you went through one a few years ago to get on that path, so hit us up in the comments with your tips and tricks!

Caveats noted, the truth is that far fewer choices are as permanent or consequential as they feel. You can probably be happy working in a number of jobs, and achieve financial success doing so even if you feel like you need to thread a needle in 2021 to “make it”. To be grossly frank, you can probably be happy with any number of long-term partners even if unrequited love right now makes you feel like you can’t breathe. In either case, finding your way will take deep work, but you by no means missed the train, another one comes every hour.

We could all do well to take a deep breath and remember this periodically. On the face of it, this realization can definitely kick off an evening of nihilism, but if you look deeper it’s actually empowering. One area where noticing this truth is particularly important is in the face of choice paralysis. Often in our quarter-life crisis we know what we must do, maybe it’s taking a new job or ending a relationship or starting a new one.

Sometimes it is the very choice that could get you out of your crisis, or maybe it’s just a step in the right direction or something you need to try. In any case, we are often fearful of dire consequences. In these instances, I’ve found it useful to not hide from that fear, but to examine it. In what is probably my favorite Ted Talk ever, Tim Ferriss outlines an exercise I’ve found incredibly useful called Fear Setting. It is an interesting twist on goal setting based on the philosophy of Stoicism in which you imagine the worst-case scenario of doing something. When you do this, it is possible you’ll find that the consequences are truly dire, and maybe you’re right to second guess yourself.

More often than not though, the downside risk is far lower than your monkey mind would have you believe, and the consequences of inaction are what you should really be afraid of. Quarter-life crisis or not, changing your relationship with fear for the better will open up a life of bold moves, experimentation, and invaluable mistakes that can be hard to access otherwise, especially if you’re a bit of a skeptic like me.

THE LIFELONG LEARNER

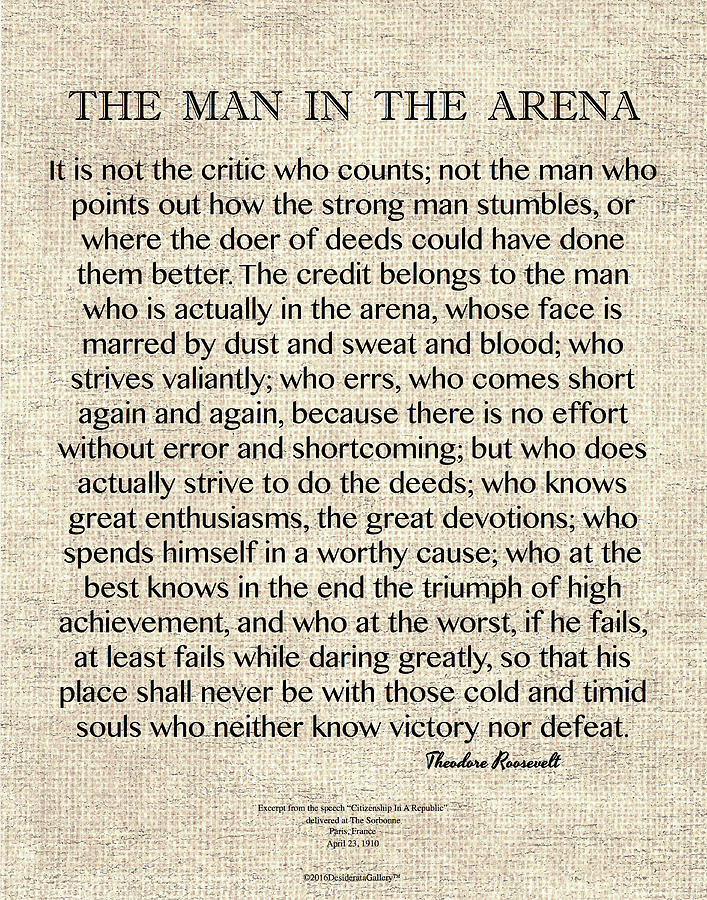

A lot of people claim to be lifelong learners, but few truly mean it. Of those who do, they are lucky if they manage to lead such a life within the confines of one successful job, one successful relationship, “one successful X”. The rest of us are here for a life of self-experimentation. For many of us the path to finding the right fit, the path to success and happiness, can only be a windy one. Victory can only be won in the arena (Appendix F). Each experience helps us understand ourselves better, shows us what we need to be fulfilled and where our talents lie, or sometimes painfully, where they don’t. In many ways, we may have no choice but to become self-experimenters, seeking out new experiences and learning from them, sometimes making bad decisions or failing.

The experimentation has a second major purpose as well, beyond its pure necessity. That is optimization. The nature of many choices requires tradeoffs, but with conscious effort you can move down a path that lets you get out of the downsides of your earlier trade without giving up the upsides. Maybe you take a job for money, but seek a promotion to a position that gives you truly satisfying work. Or maybe you start doing satisfying work and manage to generate cashflow from it later. Maybe you turn down a perfect job to be with friends, family, or a relationship and in time you find that opportunity in the city you need it to be in. Or perhaps you give those things up in search of a great job, and you take the time to build up your social network somewhere new.

The strategies for optimizing are endless. There’s the FIRE movement, the follow your heart crowd, and countless other ways to go about it. They are all valid for different people, and even the meta-strategies themselves can only be made to fit for you by tinkering.

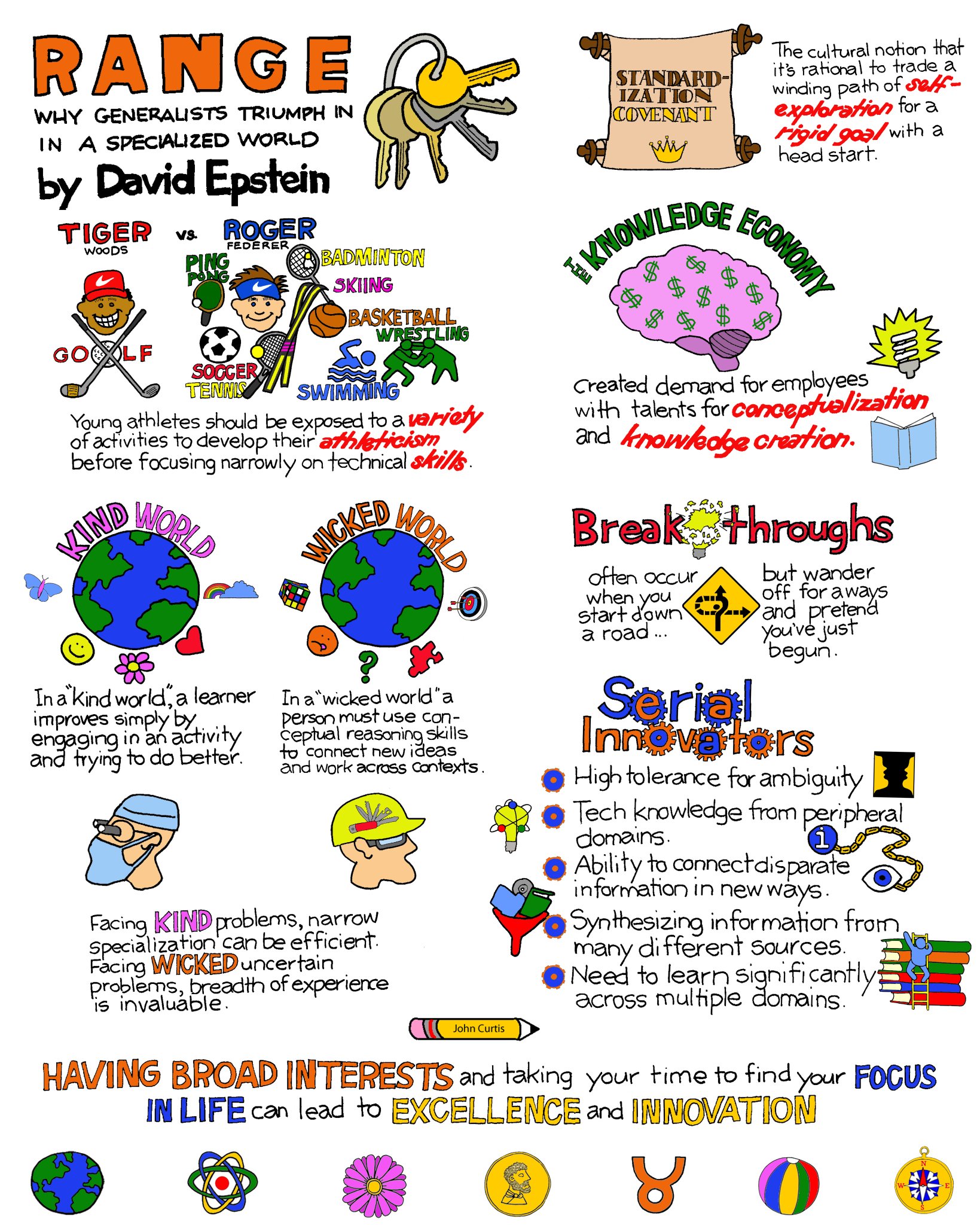

We can also take comfort that the struggles of an uncertain path do bear fruits. A book I’ve found tremendously helpful in understanding this topic is Range by David Epstein, who himself went through a very windy path from environmental science grad student to investigative journalist. I can’t say enough good things about the book, mainly because it gave me a lot of the vocabulary that I needed to think clearly and talk about some of these tough career questions.

He uses research and anecdotes to show that most high achieving, successful and happy people have re-invented themselves multiple times. He argues that going through a sampling period to find a great fit as opposed to sticking with an OK one is a better long-term strategy in many careers, especially ones that involve complex, wicked problems (Appendix C). I’d extend a lot of his logic to social and romantic relationships. In addition, the skills, relationships, and context of each new experience, even ones that were failures, are not lost. No, they make you unique and allow you to connect the dots in the way others in your eventual field(s) cannot. This isn’t to say some people don’t stick the landing early, or that you should leave a great situation if you’re in one, but it is a nice pep talk if you’re still searching in one area or another. Not only does a good quarter-life crisis not have to hurt you in the long term, it may even help (Appendix A).

While necessary and productive, navigating a quarter-life crisis is not easy. The adversity comes from two major sources. A) The tremendous uncertainty around it all, and the self-doubt, anxiety, shame, and myriad of other demons it can awaken, and B) the fact that you are in an early step of an optimization problem and you are sitting with the consequences of difficult tradeoffs.

RENOGIATING THE TRADEOFFS

The latter problem is typically a shortage of something very tangible. It could be a lack of weekends, money, human connection, meaningful work, or something else uniquely important to you. There is some evidence that our generation has had to make worse material tradeoffs than previous ones (Appendix E). There are two key ways in which we can attack this problem. The first comes quite naturally to type A people, and that is to work with the universe to renegotiate the terms of the tradeoff. That means going for the raise, extra vacation time, or the promotion as soon as you can and without giving up ground you already gained. It means having that difficult conversation with someone you love. Standard life advice is actually pretty good here, and the skills you need are well known:

- Perform exceptionally well in your current place in life, do your best

- Get really good at open and honest communication of your goals and desires with everybody (I like a lot of Brené Brown’s work on vulnerability)

- Relentlessly go for what you want, have the courage to ask for it (if this isn’t natural to you, revisit fear setting)

The other approach here that works equally well, especially if you made a tradeoff that has extreme upside for you is cycling the downsides or the Barbell technique. It’s commonly used by artists or activists who will spend several years in high-paying corporate jobs, living very frugally to pay for extended periods working on low-paying or unpaid passion projects. It’s also done by people achieving their dreams of extensive travel, or those who want to give the world to their future children, but need a solid nest egg first. Listing everything out doesn’t make it easy and life is full of curveballs. Once again and especially at this early stage, even on the meta-strategy level you need to be constantly experimenting and adjusting to figure out what works for you.

Renegotiating and continuously optimizing the tradeoffs you make to be happier and to get to a place where you can share your gifts the best is personal growth. The absolute crux to any of this is doing your best and being present in your current situation. Just because you aren’t yet in the perfect job, doesn’t mean you can’t be the absolute best employee and the hardest worker in the room. It doesn’t mean you can’t be a tremendous teammate and participate in all of the upside of being good at your job. Just because your relationship isn’t where you want it to be, or doesn’t exist at all, doesn’t mean you shouldn’t be fighting for it or working on yourself. Even if some of your friendships are transient, even transactional, that does not mean you shouldn’t be the kindest and most compassionate person they have ever met. You may accidentally open some unexpected and amazing new doors just by doing your best.

This is of the utmost importance for several reasons. First, if you are to become one of those stories of someone who took a windy path to success, someone whose journey helped them make important connections and have unique context, you need to be deeply learning from your current station in life. The only way to deeply learn is to give 100-percent effort. Moreover, the manager you do amazing work for, the friend or stranger you help, and the relationship that ends with the most compassion possible, are all people who will remember you. They may circle back in unexpectedly positive ways in the future. Even if they don’t you will look back on those interactions happy that you did them right. Lastly, and of critical importance for many of us, it will help with the former major source of adversity that comes from quarter-life crises, and help you find meaning in your journey.

THESE TRADEOFFS ARE SO UNFAIR

A major pain point here is that as so many of us are coming to terms with and renegotiating these tradeoffs, we also recognize that some of them need not be there, and it makes them sting so much more. Why does early success in some fields necessitate the total lack of work/life balance? Why do so many of the highest paying jobs involve destroying the environment or feeding a war machine? In the 30s John Maynard Keynes predicted we’d be working one day a week by now, what happened!?

Most people who go through this kind of crisis made choices early in life for the right reasons, even if somewhat haphazardly. They followed that person they loved, or didn’t because they weren’t ready. They got into medicine, engineering, law or some other exciting field to help people. Eventually, we come to a realization that to continue on the road laid with good intentions, and to do so in a thoughtful way, we need to be constantly fighting for what’s right. Fighting the good fight in this way comes in two main forms:

- The first is a ’60s hippie-style withdrawal and fight to blow up the system, to “tune in and drop out,” to be a revolutionary and make a career of calling attention to injustice and challenging power. This route is very valid, and it likely feels good to never be compromised, though it is not easy. It often involves giving up your most lucrative earning years to a cause, and in instances of an extreme stance against the powerful it can put your life and liberty at risk. It also has asymmetric returns, for every Martin Luther King, there are hundreds of people who gave up the creature comforts of a less radical life with very little payoff for anyone.

- The second is to operate within the system and use your privilege and power to help people. To argue passionately for what’s right in every meeting and memo. To lead your teams to do the same wherever you can. Ultimately you are using the “renegotiate the tradeoff” strategies above but saving some of your capital to really change things, and to put yourself in a position to help other people.

The truth is change really requires people to use both strategies, and we should not exalt one and shame another. What you should do depends on what you think you can offer each camp, and what you’re willing to sacrifice. We need good people on the outside calling out the problems, breaking the chains, and making the powerful feel uncomfortable. We also need an equal response from those who have power’s ear, or maybe even will soon be among the powerful, and are willing to listen. We need people on the street and people to write new policies, invent new products, rework how we build things, and everything in between. The same person may even operate with different strategies at different points in their journey, and there is so much real estate in between the extremes. It is not a binary problem, and you can find a slot that works for you.

I am most likely to find myself closer to camp B for the foreseeable future, and I think most of my peers are also there. This is because it’s more straightforward and despite the frustrating limitations you can do things that will help people in your growing sphere of influence. Most notably though, it’s because camp B has the promise of making a good living, which we shouldn’t feel bad about seeking. I don’t have all of the answers, or really any of them yet, but in my search I have discovered some concepts that I overlooked before.

First a few ideas I thought were obvious:

- Just committing to standing up for what’s right. Take your professional oaths seriously. Even if you didn’t formally take one, look up the oath of your chosen field, and rework it if it’s based on some outdated values. Stand up for it. For some, this means advocating for safety everywhere possible, and paying attention to it when nobody else does. For others, it means championing the environmentally right thing, or even proposing changes in company policy. This sounds like it could have some career costs, and it might. But anecdotally in the early careers of my friends and myself, I’ve seen that standing up for something only increases respect and trust for those doing it. Even when you lose the battle, you help your cause and career. This can feel quite empty at times in our entry-level gigs, as the moments to do this are few and far between and often your day-to-day work has little component of helping with some of the problems that you feel are important. The more you can grow in a job, the more you will be able to leverage this strategy for helping.

- Being a good leader who cares about people. Most people reading this will grow into leadership roles in one way or another if they haven’t already. Lean into this and learn to be great at it. Remember to take care of your people first. Several leaders in my own young career have been tremendous examples of this, and they’ve shown it to me firsthand in coaching me through my quarter-life crisis.

- Volunteer and/or Work on Helpful Side Gigs. This one is self-explanatory, but if you’re not helping people as much as you’d like at your day job, you can find a way to do it elsewhere. It’s incredibly common to build volunteering into our busy schedules while in school, and there’s no reason we shouldn’t continue those habits into adult life. Actually, as our skills and networks develop, our ability to be helpful only increases and we are probably foregoing our best volunteering years by not continuing to do it as we get older.

- Be politically active. This could vary a lot from person to person. But things will only change on a societal level if we make our governments do better.

Some ideas that were counterintuitive to me.

- Earning to Give. This is a really good strategy for someone whose talents have put them in a position to earn tremendous sums, but perhaps in a spot where they don’t really feel like they are helping anyone. You won’t be a revolutionary in your day job, though depending on where you direct the money you could be supporting those causes. When you actually crunch the numbers, giving excess income to an effective charity is one of the most impactful things you can do. 80,000hours.org does a great job breaking down how this is an underrated move and outlines a scenario in which a hedge fund manager giving away most of their money might actually have more impact than the CEO of the charity itself, even if it doesn’t feel that way to either person. They tend to align with the Giving Pledge, where people commit to giving away at least 10 percent of their income. When it comes to this approach, I am certainly a proponent of putting your own oxygen mask on first before helping others, and early-career people can and should get into the concept at far less than 10 percent.

- Choosing a career or moving to one that is objectively high impact. 80,000hours.org has numerous interesting articles on this. I list this as counterintuitive because when I was younger, I would have assumed getting into a career like this was easy, and that the higher impact jobs would be obvious to pick out but some of the analysis surprised me.

80,000hours.org has some fair criticism, and it’s actually a symptom of injustice and market failure that seeking to help people is so often done at the expense of other things that make a successful career. You also need to really consider what you will be good at and enjoy doing. At the end of the day, you are still in the position I described above, “renegotiating tradeoffs.” You just may also be doing it with some degree of altruism in your own deeply personal calculus.

THE QUARTER LIFE DEMONS AND REJECTING THE DEFERRED LIFE PLAN

While you shouldn’t let fear keep you from action to improve your situation, the reality is that a big part of the problem is that you need to operate in a less than optimal place right now, sometimes a terrible one. You need to do that to build the skills, and the social or financial capital, to get to a better spot. This doesn’t mean you should “do your time” or accept gross mistreatment, or maybe you do need to in some instances, but not for a second longer than necessary. You do probably need to make some sacrifices, go without some of your needs being met, and do some things you don’t enjoy. Life is not fair and society doesn’t have to be this way nearly to the extent that it is, but if we are to change things we need to take the world as it is.

I’ve already waxed poetically about why you shouldn’t feel shame or guilt about being where you are. Not fitting in quite perfect is normal, even admirable in a sick society, and research shows your struggles will pay dividends down the road regardless. But this does not mean that you don’t feel it, and that it won’t likely be compounded by real material failure at least a few times. The situation is genuinely uncertain, and we are hard-wired to be uncomfortable with that.

To many people the mental suffering here can be extreme, dangerous, and aggravated by other factors. So, to a large degree my take here is to seek advice elsewhere, especially if this exacerbates existing mental health problems. Leaning on your support network and ultimately finding professional help where appropriate shows tremendous wisdom and courage. Know that help is out there and that people do care.

To those with less extreme psychological suffering, I can point to some resources that I’ve found helpful. I found the blog post “Productivity” Tricks for the Neurotic, Manic-Depressive, and Crazy (Like Me) by Tim Ferriss to be quite helpful. The section attacking the “myth of successful people” is so important.

Most “superheroes” are nothing of the sort. They’re weird, neurotic creatures who do big things DESPITE lots of self-defeating habits and self-talk.

He lays out an eight-step system for getting past his demons and completing important work. It involves screen time limits, keeping a journal, a morning routine, and attacking high priority to-dos with large blocks of time. It is not universal, but I think the point is that you need to build systems and habits to bring your best self to the task at hand, even if the task is a means to an end for you. There are a ton of other resources linked in the article. Piggybacking off that, I’ve found the following practices to be immensely helpful in navigating the monkey mind day-to-day. I’m not perfect, or even good, at consistently doing them, but when I do, I’m happier, more effective, and a better friend.

- Gratitude practice (journaling, jar of awesome, meditation, writing). A lot of the suffering here comes from the hedonic treadmill. Some of us aren’t quite happy, but we are making amounts of money that we previously would have found staggering. Others are deeply happy with their day-to-day, but don’t have a dime and constantly compare themselves to friends that are growing rich. Others still may have all of the above but no one to share it with and struggle with comparisons with their friends in perfect relationships (or perfect social media). But they are dating (maybe on zoom) and seem to have forgotten that a few years ago talking to an attractive stranger would have been extremely nerve-wracking. In any case, many of us are much better off than we were a year ago but fail to notice. You are likely making progress on many fronts and will continue to even if it’s not perfectly linear. Develop a practice that lets you enjoy that journey.

- Mindfulness practice. (meditation, journaling, etc.). I’m by no means an expert here, but quarter-life crisis or not, so much mental suffering comes from being caught in negative self-talk, and there are a variety of ways you can “train” yourself to do that less.

- 10% Happier book, podcast, and app by Dan Harriss

- The Happiness Hypothesis by Jonathan Haidt

- Waking Up by Sam Harriss

- Remember Why. A lot of times in this period of our lives we find ourselves doing things as a means to an end. Whether it’s living with your parents or picking up that side gig to get ahead financially, or taking a free internship for the resume, it probably sucks bad. A) Again, that does not mean you can’t be an excellent (and poor) intern, uber driver, or live-in son/daughter, but more than that B) if the reason you’re doing it in the first place is still valid, then take a moment to remember that! Let your goals fuel you. A lot of my most shortsighted moves have involved not remembering why.

- Talk to people about it. So many of your peers are probably going through the same process. Many of your mentors have been through it in the past. If you’re open about it, they will be too. This is a group project!

- Exercise. The overwhelming research supports exercise being good for you mentally.

- Writing. This one might just be me haha

I feel the need to repeat that none of this should be construed as a cure, or a replacement for seeking real mental health treatment, or even for narrowly making positive psychology claims. Just some things that I’ve found helpful! Comment your strategies!

PARTING THOUGHTS

I write a lot of this from my own experiences, and I know I’m missing important and common aspects of it. Do let me know! This is a living document for me. I absolutely mean it as a conversation starter, and an effort to ask better questions more than anything else.

Whether or not you fit the exact model of a quarter-life crisis, almost everyone goes through several difficult transition periods in life. The fact that you are in one now is not a flaw. Actually, it is likely a bad side effect of some of your best character traits. Life isn’t a fairy tale, and moments of the journey will be truly awful, but we will adapt and overcome.

We can come out of this uniquely set up for our next chapter(s). More importantly, we can teach ourselves to be happier through this adversity and take back our prime years. Ultimately, we can carry those Zen skills throughout all the storms in life. Like anything worth doing this will require deep work and support. To that end let’s take every opportunity we can to pick each other up, dust each other off, and never let each other stop dreaming. Let’s keep our heads in the clouds, and our feet moving on the ground.

Appendix A: A few of my notes (may work into piece itself at some point)

- To repeat, this really should not at all be construed as a slight against any of my recent employers. In fact, in every case in the past few years my employers, and more importantly individual leaders in those organizations, have been amazingly supportive as I’ve navigated these waters. Several people have been real mentors to me in my young career, and in instances where I’ve gone to renegotiate my own tradeoffs, I’ve been received with tremendous openness and understanding. To the extent that I’ve made sacrifices, it’s been entirely voluntary on my part and baked into the nature of the work I’m doing right now. Work that I am enjoying. I mean this far more as a commentary on the system and the process of coming of age in 2021 than anything else.

- I’ve found a fair amount of my research quite comforting (that many successful people take windy paths, that a sampling period can be good for your career and future relationships). But at the end of the day even if some of those points were not true, my thesis that we should lean on each other and develop strategies to get through this stronger is still valid. Whether or not there are actually big silver linings, we will make the best of this together!

- I couldn’t work this into the fear setting part of the article, but some stoic philosophers, even some who were absurdly wealthy and powerful, would spend a week a month sleeping on the ground to probe out the worst-case scenarios of their bold actions.

- I have a few ideas for extending this piece, let me know if you’d like to help or contribute in some way!

- There is a ton of value in unexpected opportunities and upside that comes from uncertainty, that we almost never account for. There are probably some economists who’ve tried to quantify this one way or another, and I’m looking for research/books on the topic.

- Interviewing or even doing some podcast episodes with young people in the midst of a quarter-life crisis and/or talking to experienced people on the other side of it

Appendix B: Choosing a Career

I wanted to focus primarily on how to survive, and maybe thrive, as you navigate difficult terrain, not on which choices to make because I am no expert. But I’ve found these helpful:

- 80,000 hours blog

- Wait But Why Article: How to Pick a Career (That Actually Fits You)

Appendix C: Range and other great books

Range by David Epstein

Range is an especially fun read, packed with stories of elite cold war chess players, computer augmented game play, and windy career paths of prolific scientists, engineers, writers, and artists. It also references research to back its main claims. The relevant argument to my piece is that a sampling period, even a very long one, in which someone tries a number of different jobs or passions, is the best strategy to find a great long-term fit and can improve your ability to work on hard problems later in life.

I am no expert, and I’m sure some claims are disputed by smart people, but regardless I found the book fascinating. The most useful thing it did for my quarter-life crisis was to give me the vocabulary to understand much of the career thinking we’ve all been doing. I didn’t walk away from the book with any kind of new plan, but I did find a new sense of patience that I will figure everything out.

A Promised Land by Barak Obama

Politics aside, I found the first 10 or so chapters and the stories of his 20s and 30s to be amazingly relevant. Obama transferred colleges to find a better fit, did not attend law school until his late 20s. In his 30s he worried about being able to pay the bills and was getting bounced from after-parties at the 2000 Democratic National Convention. (Four years later, he was a key speaker).

Moreover, his storybook relationship with Michelle was not ever as easy as it comes off on television. Their relationship was packed with difficult periods of long-distance separation, and stark disagreements about what life they should lead. This is not to mention (and his book doesn’t) a few spectacular failures before he met Michelle.

To me, the value in the book was how effective it was at breaking the “myth of the successful person”. Obama had many very normal problems throughout much of his life. He questioned his purpose and direction, and his success story was not at all written for him from the beginning, nor was it even obvious in the middle.

Dying Every Day by James Romm

This is a riveting biographical narrative about Seneca, one of the more famous Stoic philosophers. He was and is considered this great moral authority, and yet he served under Nero, one of the most cruel and corrupt Roman regimes in history. It explores themes of complicity in a corrupt system and trying to change it from the inside. While telling a life story that keeps you on the edge of your seat, the book explores how power might change you or how it might not have to. Like many of us, Seneca had a ton of very tough calls to make.

Appendix D: Podcasts

The Tim Ferriss Show by Tim Ferriss

Tim Ferris made a few appearances in this piece. His podcast has been good for me over the years in just forcing me to ask myself better questions and think about my life differently.

Millennials Guide to Saving the World by Anaya Kaats

There is a lot of hippie nonsense in this podcast, and it’s not for everyone. But I do really vibe with her stated purpose. “I started this podcast because I was tired of being characterized as lazy, entitled and triggered. I started this podcast because I wanted to write a new story. One of a generation willing to challenge the status quo, embrace nuance and paradox, and reject pc culture. This podcast isn’t about finding answers its about asking the right questions….”

Making Sense by Sam Hariss

There’s a lot to this podcast! But as it relates to this piece, I’m thinking of his two conversations (that I know of) with Will MacAskill, one of the founders of the effective altruism movement.

Appendix E: Material Conditions of Millennials

Here are a few links (1 and 2) to support my claim that the material conditions of young adults are worse today. Though this isn’t really my main thesis and I imagine people have been going through this experience for all of history.

Appendix F: Man in the Arena Speech and Brené Brown

The Man in the Arena is an excerpt from a speech titled Citizens in a Repbublic by Teddy Roosevelt. It’s a decent approximation of my life philosophy. I believe I first heard it in a Brené Brown talk and Lebron writes the words on his gameday shoes sometimes. Brené also has a ton of amazing work on shame, vulnerability, and navigating the modern world.