An analysis of the macroeconomic policies of George W. Bush in response to extraordinary crises

This is the most interesting piece that I have ever written for school, at least if you’re an economics nerd like me. With my political leanings, I was ready to write a scathing piece (and in many ways I still did), but I was astounded by how difficult the problems Bush faced really were, and how nuanced my analysis had to be. It was a great exercise in making an argument using real-world data, academic theory, and logical reasoning. It’s very, very long. Feel free to reach out if you’d like to see any appendix material, have a question, or would like to talk more about any of it.

Introduction

Many events happened during the Bush years that will come to define our generation. For better or worse, George W. Bush navigated the free world through two expensive wars, two large recession events and the worst terrorist attacks in American history. In the wake of the attacks on September 11th, 2001 Bush said “The resolve of our great nation is being tested, but make no mistake. We will show the world that we will pass this test.” These words were a rally cry and a challenge for American leaders in every walk of life including our generals, our cultural icons, our intellectuals, and our economic policy makers. While these words were said in response to the terrorist attacks that day, the sentiment of the need to overcome great challenges together could have applied large parts of Bush’s 8 years in office, not the least of which would be the two recessions faced during our first decade in this new millennia. Truthfully, we are in need of that same sentiment today.

In the wake of the Great Recession the public opinion of history, at least as the mainstream media tells it, does not tend to look back very kindly on the policies of George W. Bush. However, in the spirit of unity that Bush inspired in us during one of the countries darkest hours, it is wise to take a more nuanced look at the administration’s economic policies and the real world data to discern truly what impact they had on the country. By telling the story of the administration from the starting conditions through the great recession, discussing the theoretical underpinnings of the important policy decisions, and looking at the outcomes of those choices we can learn a great deal about how to face changing economic climates today and in the future. Without having this conversation, we will lose ourselves in partisan banter and have no real hope of learning from the past.

Background Conditions-The Roaring 90s

The background conditions at the beginning of the presidency could best be described by Bush’s predecessor, Bill Clinton, in his February 2000 Economic Report of the President. With the opening paragraph he remarks:

Today, the American economy is stronger than ever. We are on the brink of marking the longest economic expansion in our Nation’s history. More than 20 million new jobs have been created since Vice President Gore and I took office in January 1993. We now have the lowest unemployment rate in 30 years—even as core inflation has reached its lowest level since 1965.

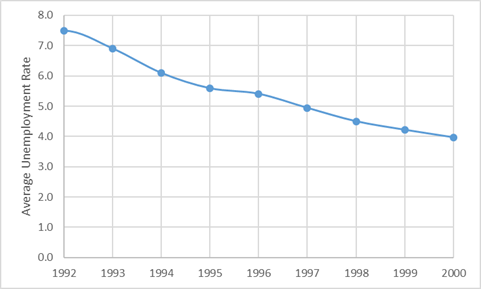

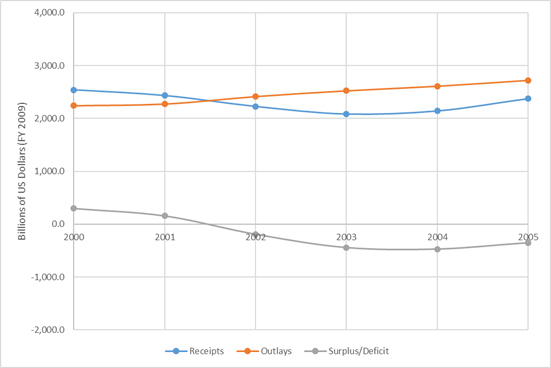

Looking at the historical data in Figure 1, he was not lying about the healthy jobs growth. Indeed almost every assessment of Clinton’s economy in the 1990s looks rosy, with low unemployment, low inflation, high GDP growth, and a government surplus. Four for four on the key macro-economic variables.

See figure A1 and A2 in Appendix for more comprehensive economic data of the Clinton era.

This amazing success was largely driven by globalization and rapid technological advances, particularly those associated with advent of the internet and the new information age. Acknowledging these two key factors the Clinton administration also attributed this economic success to “fiscal discipline to help reduce interest rates and spur business investments” (United States Government Printing Office. “Economic Report of the President.” 2000), running the first budget surplus in almost 50 years. In the backdrop of this prosperity Bush ran a campaign for “compassionate conservatism” based on seizing “this moment of American promise”, vowing to “reduce tax rates for everyone, in every bracket” while also expanding programs to help the poor (“Acceptance Speech | President George W. Bush | 2000 Republican National Convention.” ). Had Bush continued to enjoy the economic growth and government revenue levels of the 1990s, much of what he had promised may have been feasible, but as any novice student of the business cycle might tell you long expansions are almost always followed by economic downturns.

Bush Administration Macroeconomic Policy Story: A Response to Crisis

2000 Recession

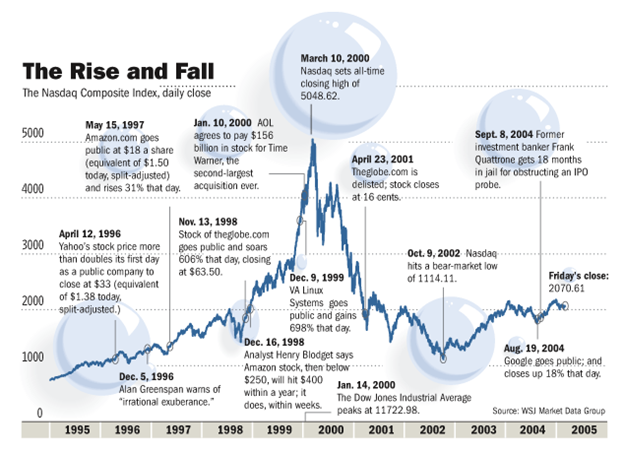

In the last half of 2000, just has Clinton was preparing to ride off into the sunset, the economy began to stagnate. This was largely due to a technology investment market correction commonly coined the “dot-com” bubble in which there was a “land grab” for various internet business sectors (i.e. search, social networks, etc.). In order to gain the first mover advantage companies with bad finances prematurely asked for private investments and filed for IPOs, and investors poured their cash in. When many of these companies failed to get past the idea stage the bottom fell out of the stock market. In March 2000 the NASDAQ had set an all-time high, but in the latter half of the year it dropped quite rapidly and within months of Bush entering office the economy had officially entered a recession (Amadeo). Unfortunately things would get worse before they got better.

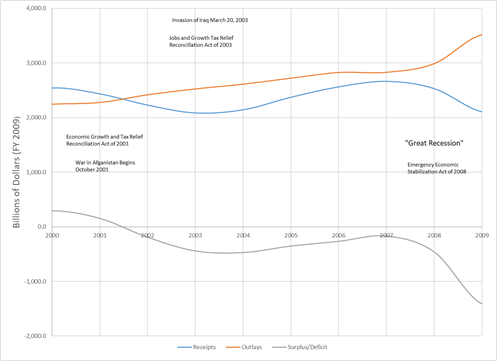

To quote the Federal Reserve’s Monetary Policy Report of 2002, 2001 was a “difficult one (year) for the economy of the United States.” (Monetary Policy Report to Congress). With a recession on his hands, Bush responded by quickly meeting his promise to cut taxes with the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001 (EGTRRA) and the Federal Reserve engaged in open market operations and reduced the discount rate to pump money into the economy. Among other changes to the tax code, EGTRRA was a broad reduction in individual income tax rates in all brackets as well as reductions in capital gains taxes. While he originally intended to cut taxes to give surpluses back to the people, his tax cuts were now a discretionary measure to jump start a stalled economy. Bad luck continued to pile on Bush with the jarring and unexpected September 11th terrorist attacks which led us into invasions of Afghanistan later that year.

While the tax cuts and expansionary monetary policy seemed to spur some new growth, the unemployment rate was unsatisfactory by the end of 2002 with Bush describing the economy as such:

Despite these challenges, the economy’s underlying fundamentals remain solid— including low inflation, low interest rates, and strong productivity gains. Yet the pace of the expansion has not been satisfactory; there are still too many Americans looking for jobs. (United States Government Printing Office. “Economic Report of the President.”

2003)

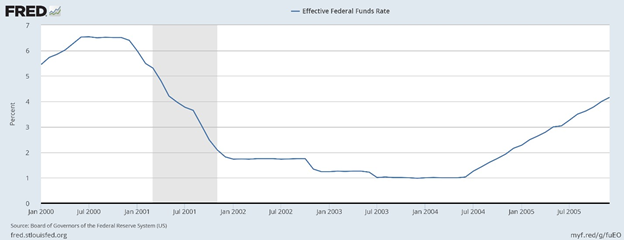

A couple macroeconomic variables in line is not good enough to rest easy, especially when the one out of whack is employment. The administrations answer to this “jobless recovery” was the Jobs and Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2003 (JGTRRA), which along with EGTRRA would be the second of the two “Bush Era Tax Cuts”. JGTRRA further decreased taxes for higher income brackets, decreased capital gains taxes, and accelerated the aspects of EGTRRA that were originally intended to be phased in. While cutting taxes, Bush simultaneously ramped up military spending for the invasion of Iraq in March 2003. On top of this additional fiscal stimulus the Federal Reserve continued to engage in expansionary monetary policy to get the job market to start growing again (Figure 3).

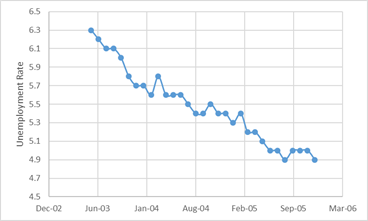

Whether by the merit of the looser fiscal and monetary policy (Kraay et. al), by getting past the “correction” of the dot com bubble, or by the ebb and flow of the business cycle, the economy did begin to experience solid jobs growth in 2004 and in 2005 Bush declared in the opening statement of his Economics Report that “The United States is enjoying a robust economic expansion because of the good policies we have put in place and the strong efforts of America’s workers and entrepreneurs.” As seen in Figure 4 the job market did indeed recover in the latter half of 2003 into 2004, likely helping Bush win his bid for reelection in November 2004.

The victory of getting Americans back to work did not come for free. The economic recovery and expansion of the mid 2000s was characterized by a large decrease in tax receipts, leaving no doubt which side of the Laffer Curve the American public was on. On top of that, two wars drove up spending leading to very large deficits.

Figure A4 in appendix tracks economic growth alongside deficit for this time period and figure A3 shows the receipts, outlays, and the deficit over a long time scale for perspective.

2008 Financial Crisis

Unfortunately for the administration and for the people of the world, this expansionary period did not last exceptionally long. A new “bubble” had formed in the economy by the mid2000s, this time in the housing market. Housing prices rose at an unsustainable rate as people got easy credit to buy property that they could not truly afford. Through series of perverse incentives and complicated new, unregulated financial instruments, many large American financial instructions were exposed to an unreasonable amount of risk associated with the housing market. When the housing market crashed in the 2007 sub-prime mortgage crisis, catastrophically, it was soon followed by the collapse of Bear Sterns, Lehman Brothers, and a number of other formerly trusted banking institutions in 2008. This kicked off what many call the worst recession since the 1930s, now commonly coined the “Great Recession”.

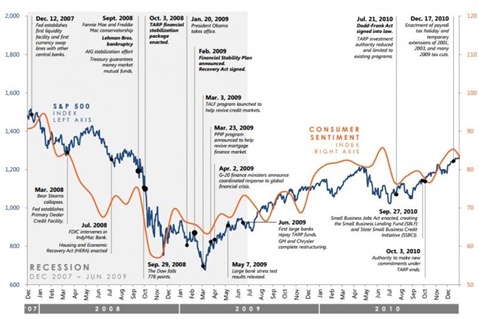

Unsurprisingly Bush’s initial response was fiscal stimulus through discretionary tax policy. This time it was in the form of the Economic Stimulus Act of 2008, which constituted a tax rebate for most tax payers in the hope of boosting consumer spending. This act returned $96 billion to the people in April of 2008 (“Fact Sheet: Bipartisan Growth Package Will Help Protect Our Nation’s Economic Health .”). As the economy continued to crumble Bush supported the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008, now commonly referred to as the “bank bailout”. This was a large bill containing many provisions. First in an effort to increase confidence in banks it increased FDIC insurance from $100,000 to $250,000. Additionally, it expanded the Federal Reserves ability to enact monetary policy by allowing the Fed to pay a higher interest rate on banks deposits with it. Most significantly and most controversially, it allocated $700 billion in federal spending for the Troubled Assets Relief Program (TARP). In this program the federal government bought up “toxic assets” and equity from financial institutions to strengthen consumer confidence in the remaining assets and keep the financial sector from collapsing. In its execution, this program made up the much-criticized loans and capital injections that constitute the bailouts of the financial sector and the auto industry. In addition it provided relief to homeowners in the form of foreclosure assistance. The vast majority of these loans were eventually paid back with interest, netting a small profit for the government.

In addition to the controversial bailout the Federal Reserve also engaged in controversial monetary policy, taking interest rates to essentially zero in order to encourage investment (Figure A6 in appendix shows discount rate over this period). In addition to the usual open market operations and other policy tools, the Fed engaged in a new practice called quantitative easing. The Fed bought up long term government bonds and other real assets with electronic money that didn’t really exist before in an effort to drastically increase the money supply. The practice is often coined “printing money” by critics.

Unfortunately for Bush, if he cares about his legacy, his term ran out before any effect of these policies became noticeable, especially to working class Americans trying to get by. He passed the torch on to Barack Obama, who continued Bush’s stimulus policies that slowly but surely dug the country out of the recession. Bush would end his presidency with some of the lowest approval ratings of all time, and years after he left office many of his political opponents, media pundits and even some people in his own party would blame him for the recession. Figure A5 in the appendix shows the terrible growth rate and huge deficit spending over this period.

Theoretical Underpinnings: Keynesian in a Crisis

When Bush ran for president in 2000 the general consensus, though not totally unquestioned, was that supply side policies were the best way to grow and maintain a healthy economy. This was especially true in his Republican party. This line of thinking was kicked off intellectually by Milton Friedman and the monetarist counterrevolution. It gained political capital and credibility among policy thinkers in the early 1980s with Ronald Reagan’s deregulation, non-discretionary tax cuts and tight fiscal policy in the United States, and perhaps even more so with Margret Thatcher’s pursuit of tight money and balanced budgets in Great Britain. For better or worse, in the mainstream media “Reaganomics” and “Thatcherism” were largely credited with ending a period of terrible stagflation and kicking of the “Great Moderation”, a long period of greatly reduced volatility in global macroeconomic variables (“How Mrs Thatcher Smashed the Keynesian Consensus.”). These ideas continued to dominate economic thought policy in the United States for the next two decades. George H.W. Bush, George W. Bush’s father, was Reagan’s vice president and a natural successor who continued his policies. While it is unlikely that Democrats would frame their policies as in any way in line with Reagan or Thatcher, the highly effective and ready to compromise Clinton administration largely continued to develop their policies with similar theoretical underpinnings. Working closely with Newt Gingrich and a Republican congress, their relatively tight monetary policy, fiscal conservatism and a focus on technology and competition was fundamentally a supply side approach that had become conventional wisdom at that point.

Bush rarely waxed eloquently on macroeconomic details, but he was a clear admirer of Ronald Reagan and is a proud member his conservative political lineage. To this day Bush periodically speaks at the Reagan Institute. Bush’s “compassionate conservatism” had the same everyman’s charm as Reaganomics as it was pitched on the campaign trail. Furthermore, it shared the somewhat hard to pin down theoretical basis in that it loosely stood for the spirit of free market supply side economics, though their opponents could always point to their loose fiscal policy as secretly Keynesian. The major macroeconomic policy prescription of both men was of course non-discretionary tax cuts, which seemed like a great idea in 2000 to many supply side thinkers and to voters in battle ground states. In the backdrop of budget surpluses, these tax cuts would be fiscally reasonable in simply giving the left over money back to the people, which they would use to generate even more economic growth. There was even some who thought that cutting taxes could generate even more revenue as economic growth would drive up incomes.

As we know the bright economic conditions Bush ran his campaign under did not last and his policies were more a series of discretionary responses to crisis than a broad systematic improvement. The 2000 recession represented a serious shock to the confidence in the monetarist assumptions both sides of the aisle had been operating under (Levine). This is reflected in a change in Bush’s language from “returning surpluses to the people” to getting Americans back to work, even if large deficits were necessary. The 2001 EGTRRA and 2003 JGTRRA tax cuts were now clearly a fiscal expansion, with dates set for them to expire after the economy had recovered (Weller et. Al). In a similar way the chairman of the Federal Reserve Alan Greenspan, a self-described libertarian and friend of Ayn Rand, had some change of heart and engaged in expansionary fiscal policy. With the climb out of that recession lending some evidence that these interventionist policies were effective, Bush decided to nominate a New Keynesian as the next chairman of the Federal Reserve in 2005, Ben Bernanke.

If the 2000 recession called into question the monetarist assumptions, the Great Recession of 2008 destroyed them in the minds of the administration’s policy makers. Even if you could shrug off the Bush era tax cuts as fundamentally supply side, the administration’s and the Federal Reserve’s response to the Great Recession was unabashedly Keynesian. The policy response of drastic and unconventional monetary expansion, targeted discretionary tax relief, fiscal spending stimulus, and institutional bailouts was openly interventionist, and it represented a complete break from the monetarist consensus that dominated the twenty years prior to Bush. In response to critics of his approach, in his last month in office Bush famously said “I’ve abandoned free market principles to save the free market system” (argufest), admitting that his policies represented a stark shift away from his core principles that he believed was necessary to save the American economy. Barak Obama and the Democratic congress, who inherited these problems, agreed, and continued with the same Keynesian policies.

Outcomes: Avoiding Calamity and Living with Mistakes

Courage in the Face of Crisis

One would have a hard time claiming that the economic policies of George W. Bush were stellar given the fact that he entered the White House at the end of a long economic expansion with budget surpluses and left it at the start of the worst downturn since the Great Depression. As stated in the opening of this paper, a more balanced approach should certainly be taken. The administration’s flexibility with regard to economic thinking allowed them to pivot to a more interventionist mindset in response to crisis, while still selling the political idea of tax cuts to the conservative base. There is some evidence that the tax cuts helped the economy pull out of the 2000 recession (Kraay et. al) and there is strong case to be made that the incredibly unpopular interventionist policies in response to the banking crisis saved the world from another Great Depression.

While Bush may have done well with intervention, his record of prevention is dismal. There is a good case to be made that among other factors the deregulation of the banking industry in the 1980s set the stage for the crisis in 2008 (Bentley). Bush had swallowed the conservative orthodoxy of light regulatory policy that allowed small structural problems in the economy to continue to grow. While Bush did not make those policies, his administration and nearly everyone in the world failed to see the warning signs that thing were breaking down.

A Lasting Legacy: Deficit Spending

Perhaps the most scathing critique of Bush’s policies has been the lasting effects of the tax cuts, and to a much lesser degree the war spending, on the deficits long term. Looking at the data it hard to ignore the instant drop in tax receipts that came from the EGTRRA tax cut in 2001.

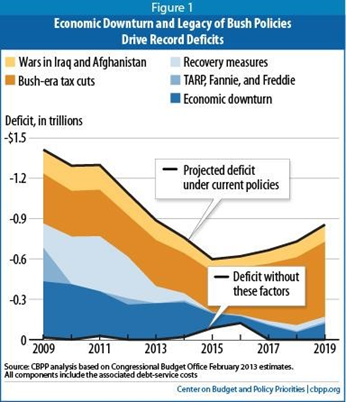

The Bush era tax cuts were extremely hard to reverse politically, and the War on Terror has dragged on for over a decade now. These polices have imposed a structural deficit that was exacerbated due to recovery spending in the 2008 recession. The result of this has been deficits not seen since World War II. The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (Ruffing et. al), and many others, have done analysis on Bush era policies impact on the deficits to this day, and their conclusions have been rather scathing of Bush. Ruffing states:

The goal of reining in long-term deficits and debt would be much easier to achieve if it were not for the policies set in motion during the Bush years. That era’s tax cuts — most of which policymakers extended in this year’s American Taxpayer Relief Act, with President Obama’s support — and the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan will account for almost half of the debt that we will owe, under current policies, by 2019 (Ruffing 2)

Bush’s legacy of structural deficits surely left the country in a weaker position to recover from the Great Recession as the Obama administration could not afford to have as big a stimulus package as they would have liked. No doubt the deficit will haunt us again the next time stimulus spending is needed to get through a trough in the business cycle.

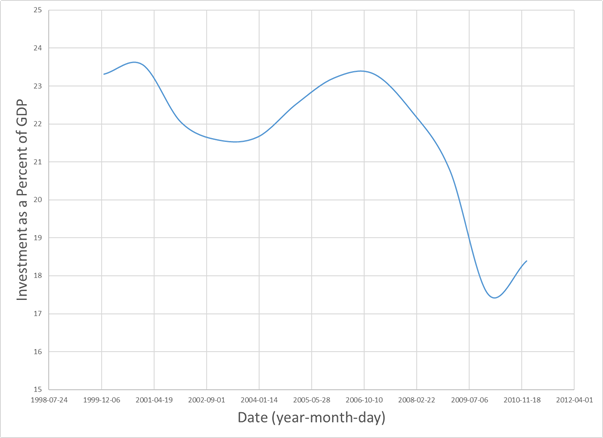

Facing the economic and social challenges of becoming a country with true universal healthcare, supporting an aging population, addressing growing environmental concerns, dealing with the advent of general artificial intelligence, and rebuilding our crumbling infrastructure will likely require large public and private investments in education, health care, technology and infrastructure. Obviously with large deficits and the expense of interest on the debt, the government cannot lean into these challenges with targeted public investment as much as many would like it to. On an even deeper level, deficit spending has likely hurt private investment needed to meet these challenges due to the crowding out effect and the behavioral effects of tax cuts on national saving (Auerbach). While it is very hard to build a causal relationship between the tax cuts and national investment because so many variables are involved, there has definitely been a decrease in investment as a percent of GDP starting in 2001. (Figure 9). This no doubt hurts the nation’s long-term growth and employment prospects, and keeps the overall wellbeing of the people from being everything that it could be.

Conclusion: A Lesson for the Next Generation

The economy during the Bush administration was story of great extremes, and treasure trove for a researcher who wants to look at the whole boom and bust cycle. Bush entered office during one of the most prosperous times in American history and immediately saw the country through the jarring dot-com bubble and the 2001 terrorist attacks. After recovering from that Bush arguably saved us from the brink of another Great Depression through the bailouts of the financial system.

In the spirit of learning from our mistakes, this analysis must be rather scathing of Bush policies in some respects, particularly with regard to the structural deficits his policies created. It should be granted that the war in Afghanistan and the Great Recession bailouts were largely unavoidable, but we cannot give a pass on the tax cuts and the war in Iraq. While it was a relatively small part of the deficits and the foreign policy and moral arguments needed to fully tackle this issue are perhaps beyond the scope of this economic analysis, most students of recent history cannot shake the feeling that the war in Iraq was a senseless waste of money and lives. In hindsight, the trying to secure weapons of mass destruction that didn’t exist seems like a gross foreign policy mistake at best. The money that went into toppling and rather unsuccessfully rebuilding Iraq over a decade would have been better spent investing in American infrastructure, education and technology. Even more significantly in terms of its impact on the deficit, the large tax cuts were a political promise that Bush should not have kept, though he realistically had to in order to stay in office. It would have been wiser to use targeted stimulus spending to drive us out of recessions, instead of a seemingly irreversible tax cut with a corresponding structural deficit that haunts us to this day and likely will for years to come.

While many would be happy to brutalize Bush further for his failure to stop the Great Recession, it would be hard to make the case that he could have stopped it as almost nobody saw the crisis coming. While he didn’t prevent it from happening, Bush demonstrated poise, courage, and an openness to unconventional ideas in the face of several terrible crises. Bush should be commended for his courage to break from the conservative party line, the popular consensus, the intellectual status quo and even his own core principles to do what he thought was best for the country. As our leader, he brought the country together after the devastating terrorist attacks of September 11th, and was willing to abandon conservative dogma in order to save us from another Great Depression. We should be careful to learn from both Bush’s policy missteps, and from his character in response to adversity. By doing this on a personal and national level, we can find ourselves making better decisions and achieving a greater good.

Figures A7, A8, and A9 in the Appendix show the key macroeconomic variables from a broad historical perspective. Feel Free to Reach Out for a complete PDF including the appendix figures!

Bibliography

- “Acceptance Speech | President George W. Bush | 2000 Republican National Convention.” YouTube.

- YouTube, 07 Mar. 2016. Web.

- Amadeo, Kimberly. “11 Recessions Since the Great Depression.” The Balance. The Balance, 22 Aug.

- 2017. Web.

- Argusfest. “I’ve Abandoned Free Market Principles to save the Free Market System” – George W.

- Bush.” YouTube. YouTube, 14 Jan. 2013. Web.

- Auerbach, Alan J. “The Bush Tax Cut and National Saving.” NBER Working Papers Series (2002): n. pag. Web.

- Bentley, Katherine. The 2008 Financial Crisis: How Deregulation Led to the Crisis. Lake Forest

- College Publications, 4 Apr. 2015. Web.

- “Effective Federal Funds Rate.” Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US).

- “Fact Sheet: Bipartisan Growth Package Will Help Protect Our Nation’s Economic Health.” National

- Archives and Records Administration. National Archives and Records Administration, n.d. Web.

- Frankel, Jeffrey, and Peter Orszag. “Retrospective on American Economic Policy in the 1990s.” “Historical Tables.” The White House. The United States Government, 23 May 2017. Web.

- “History of the Financial Crisis: Mid-2007 to 2010.” Pbs.org. PBS, n.d. Web

- Kraay, Aart, and Jaume Ventura. “The Dot-Com Bubble the Bush Deficits, and the U.S. Current

- Account.” NBER Working Papers Series (2005): n. pag. Web.

- “How Mrs Thatcher Smashed the Keynesian Consensus.” The Economist. The Economist Newspaper,

- 09 Apr. 2013. Web.

- “Inflation, Consumer Prices (annual %).” Inflation, Consumer Prices (annual %) | Data. The World

- Bank, n.d. Web.

- Levine, Robert A. “The Economic Consequences of Mr. Clinton.” The Atlantic. Atlantic Media

- Company, 17 Jan. 2017. Web.

- Monetary Policy Report to Congress. Publication. N.p.: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve

- System, 2002. Print.

- Price, Robert W. “What Caused the Internet Bubble of 1999?” Global Entrepreneurship Institute.

- Global Entrepreneurship Institute, 08 Aug. 2016. Web

- Ruffing, Kathy, and Joel Friedman. “Economic Downturn and Legacy of Bush Policies Continue to Drive Large Deficits.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Center on Budget and Policy

- Priorities, 10 June 2015. Web.

- United States Government Printing Office. “Economic Report of the President.” 2005 ed. Washington, D.C.: GPO, February 2000.

- United States Government Printing Office. “Economic Report of the President.” 2005 ed. Washington, D.C.: GPO, February 2003.

- United States Government Printing Office. “Economic Report of the President.” 2005 ed. Washington, D.C.: GPO, February 2005.

- “United States Total Investment, % of GDP.” Quandl.com, IMF Cross Country Macroeconomic

- Statistics.

- US Department of Commerce, BEA, Bureau of Economic Analysis. “National Economic

- Accounts.” BEA. U.S. Department of Commerce, n.d. Web.

- Weller, Christan, Josh Bivens, and Max Sawicky. “Macro Policy Lessons from the Recent

- Recession.” Challenge 47.3 (2004): n. pag. Web.